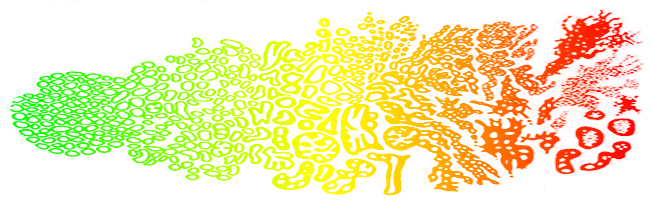

Risk Categories: The Spectrum Within the Spectrum

The low, intermediate, and high risk breakdown of prostate cancer severity established by Dr. D’Amico has proven invaluable in establishing the therapy necessary for each risk category to achieve cure; however, within each category there is a spectrum of severity. On one end of each category is minimum disease severity, and on the other end is a maximum. Treatment recommendations may change to account for these subtle variations within each category. For this reason, broad generalizations about the best treatment for prostate cancer are unhelpful.

The modern approach is to individualize treatment. This means that the optimal approach for the same cancer in one man may be different in another. For example, a 55 year old man with low risk cancer may elect aggressive therapy, while a 75 year old might elect to "watch and wait."

The best approach for a man seeking to understand his illness is to begin by calculating his risk category, then determine if he is at the high or low end of this category. The treatment options for that degree of cancer will vary, but it should be possible to create a short list of proven options. After that, the decision is based on the individual and what makes the most sense to him after a discussion with a doctor he trusts.

Low Risk

Low risk cancers are highly curable and very unlikely (less than 1% of cases) to spread. Within the low risk group is what might be termed ultra-low-risk prostate cancer. Such men technically have cancer, but the amount very low (only one or two biopsies positive), or a PSA level of less than 4. A man in such a situation should strongly consider deferring treatment. As long as the cancer is treated before the PSA reaches 10, cure rates are extremely high.

At the other extreme of low risk are men with many biopsies positive (more than 50% of cases) and signs of more aggressive behavior. In such cancers the malignant cells invade the space surrounding a nerve, a feature termed perineural infiltration. Also, if the PSA is close to 10 then there is very little room to watch and wait before the PSA reaches 10, the trigger for treatment. Patients with this form of low risk cancer are not well served by "watch and wait" and should consider treatment.

In between these extremes are men with highly curable cancer who are still candidates for deferred treatment. Although not as ideally suited for deferred treatment as the ultra-low-risk group, they certainly have time to make a careful decision and should not be rushed into treatment.

There are two strategies to try to determine if these men are harboring more aggressive disease.

One approach is called saturation biopsy. In this procedure men are anesthetized and the entire prostate is biopsied exhaustively in search of Gleason 7 or higher disease that would move them out of the low risk category. If the saturation biopsy shows no proof of disease beyond Gleason 6 they may continue to monitor their cancer without treatment.

The second approach is an MRI with multiple scan sequences. With this type of scan it is possible to actually see the tumor areas and determine if they appear more aggressive than Gleason 6. If more aggressive disease is apparent deferred treatment is no longer a reasonable choice.

In addition to information about the cancer, MRI can provide information helpful in choosing between treatments. For example, sphincter length can be easily measured and can predict urinary incontinence following surgery. Nerve bundle anatomy and location can predict whether sexual function can be preserved with the standard nerve sparing operation. Some men have an unusual form of prostate enlargement called a median lobe, and this can clearly be seen on MRI. Such men are likely to have greater difficulty with a seed implant approach.

Intermediate Risk

Intermediate risk cancers are almost always treated and are highly curable with appropriate therapy. Within this category are men with minimally aggressive disease who can be effectively treated with less intensive therapy. Such men are one small step beyond low risk. For example, if a biopsy reveals a Gleason score of 3+4 instead of 3+3, that cancer would be considered intermediate risk. If a man were low risk by exam and Gleason score, but his PSA is 12 instead of 9, he would be intermediate risk. In terms of prognosis, men with minimal intermediate risk features are as curable as low risk men and may not need aggressive therapy. Watchful waiting has been studied within this group; but most men with these factors select treatment.

On the other extreme are men with all three traits of intermediate risk: a PSA >10, a Gleason score of 4+3, and an exam with disease than can be felt on both sides of the prostate. A man with those traits who also has biopsies that are over 50%positive would be at the maximum end of intermediate risk. Such men may require intensive therapy and could be treated the way high risk patients are treated, with a combination of therapies (hormones plus internal plus external radiation, or surgery plus external radiation) depending on the specific features of the disease.

Between the two extremes are men with mid-range disease that may be treated less or more aggressively at the discretion of the patient or his physician. Some men may be inclined to want aggressive therapy with extremely high cure rates and not worry as much about temporary side effects, while others will choose treatment with a high success rate but fewer side effects, reserving some treatments for backup.

MRI scans can be extremely valuable in treatment decisions. If the disease extends beyond the gland then prostate-only treatments such as surgery and seed implants may not be sufficient, and beam radiation may be necessary to eradicate these cells.

In addition to information about the cancer, MRI can provide information helpful in choosing between treatments. For example, sphincter length can be easily measured and can predict urinary incontinence following surgery. Nerve bundle anatomy and location can predict whether sexual function can be preserved with the standard nerve sparing operation. Some men have an unusual form of prostate enlargement called a median lobe, and this can clearly be seen on MRI. Such men are likely to have greater difficulty with a seed implant approach.

High Risk

High risk cancers are always treated and may require aggressive therapy to achieve cure. Although the term high risk is alarming and anxiety-provoking, with appropriate therapy the majority of men are cured. Within the category are men with minimal high risk features, one small step beyond intermediate risk. For example, if one biopsy is 4+4 instead of 4+3 the cancer would be considered high risk. A PSA of 22 instead of 18 would also indicate high risk. If only one of the three high risk features is present, this represents a minimal high risk cancer requiring less intensive treatment than others in the high risk group.

On the other extreme are men with all three high risk features: a PSA >20, aT3 exam and a Gleason of 9 or 10 with > 50% biopsies positive. This group will require both local and body wide treatment (hormone therapy). The hormone therapy required may be 2 years in duration, which can cause a wide range of symptoms. Regardless of side effects, hormone therapy is worthwhile. Studies suggest a survival advantage for men treated with hormones combined with beam radiation compared to those treated with beam radiation alone.

In between the extremes of minimum and maximum high risk cancers are men with two high risk features, and an individualized approach is appropriate. The ongoing debate is whether 2 years of hormone therapy are necessary. Some studies suggest 6 months of hormone therapy may be sufficient in this group. Other studies suggest that when internal radiation is combined with beam radiation to intensify the dose delivered to the prostate and surrounding tissues, hormone therapy is not as critical to outcome, or a shorter duration may be sufficient. If surgery is elected for high risk disease, there is a very strong likelihood that radiation will be required afterward to eradicate any cancer cells beyond the prostate.

MRI is extremely valuable in evaluating high risk cancers. The scan may demonstrate the extent of the cancer and this may be very valuable in treatment planning. For example, if internal radiation is planned a higher dose can be delivered specifically to tumor areas to improve the outcomes. If a tumor extends beyond the prostate and involves the nerves responsible for erections, nerve sparing surgery may not be feasible or desirable.

In addition to information about the cancer, MRI can provide information helpful in choosing between treatments. For example, sphincter length can be easily measured and can predict urinary incontinence following surgery. Nerve bundle anatomy and location can predict whether sexual function can be preserved with the standard nerve sparing operation. Some men have an unusual form of prostate enlargement called a median lobe, and this can clearly be seen on MRI. Such men are likely to have greater difficulty with a seed implant approach.

Metastatic Disease

Within the last 3 to 5 years the outlook for men with metastatic disease has changed dramatically. Three important new treatments have been tested and found to be effective The list of “backup to the backup” options continues to grows The usual approach is hormone therapy rather than local therapies, but a recent study suggests a well-tolerated form of chemotherapy combined with hormone therapy worked better than the standard hormone therapy alone.

The shift from treatment-to-cure to treatment-to-control, and from the goal of cure to the goal of remission, is a significant psychological hurdle made easier by the wide variety of approaches available. The progress in treatment for incurable cancers is not exclusive to prostate cancer. The greatest progress in cancer treatments in general in the past 10 years has been the addition of more effective “backups to the backups” that have made it increasingly difficult to give a meaningful prognosis in time for cancer patients with metastatic disease.